How to Hack Assault Cube – Beginner’s Guide to Game Hacking (Part 2)

Author: Alcidius

August 27, 2025

If you haven’t read Part 1 of this Assault Cube hacking series I recommend starting there first. In that guide, we covered the reverse engineering basics, uncovered the game’s key memory structures, and documented several critical offsets:

- Local player object:

"ac_client.exe"+0018AC00; - Entity list:

"ac_client.exe"+0018AC04; - Entity count:

"ac_client.exe"+191FD4; - Head coordinates offset:

0x0004; - View angles:

0x0034.

In this post, we’ll take those discoveries and use them to actually build a working aimbot in Assault Cube. You’ll learn how to automatically attach to the game process, fetch the local player pointer, calculate vectors, and write view angles so your aim snaps directly to the nearest enemy.

If you’d rather skip ahead, you can find the full aimbot source code on GitHub here.

Creating an Aimbot

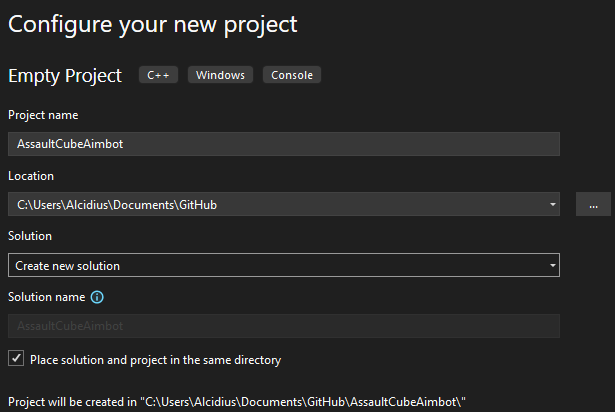

he first step in building an aimbot in Assault Cube is setting up our coding environment. I’m using Visual Studio, but you can use any IDE or compiler you’re comfortable with. Personally, I prefer a Make project over the default Visual Studio solution since it keeps things cleaner in the long run, but both approaches work fine.

Inside the new project, create a

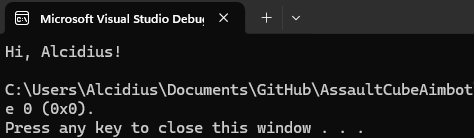

Inside the new project, create a main.c file. To make sure everything is working, I add some basic includes and a simple test program:

#define UNICODE

#define _UNICODE

#include <math.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <Windows.h>

#include <TlHelp32.h>

#include <psapi.h>

#include "offsets.h"

int main()

{

printf("Hi, Alcidius!\\n");

return 0;

}

Looks good, we’re compiling and running fine.

Looks good, we’re compiling and running fine.

Next, let’s set up a dedicated header file called offsets.h to store the values we discovered in Part 1. Keeping them in one place makes updating offsets easy if the game version changes:

#pragma once

/**

Assault Cube Version 1.3.0.2

**/

#define LOCALPLAYEROFFSET 0x18AC00

#define ENTITYLIST 0x18AC04

#define ENTITYLISTCOUNT 0x191FD4

#define PLAYERHEADPOSOFFSET 0x0004

#define PLAYERYAWOFFSET 0x0034

#define PLAYERPITCHOFFSET 0x0038

Automatically Attaching to the Assault Cube Process

Instead of manually attaching to Assault Cube with Cheat Engine every time, we’ll automate the process by writing code that finds and attaches to the game process at runtime. This makes our aimbot setup seamless whenever the program launches.

To do this, we’ll rely on a few key WinAPI functions:

- CreateToolhelp32Snapshot: takes a snapshot of all running processes;

- wcsicmp: compares process names, so we can match against

ac_client.exe; - Process32First: Retrieves information about the first process encountered in a snapshot;

- Process32Next: Retrieves information about the next process recorded from

CreateToolHelp32Snapshot.

We’ll wrap this in a helper function called GetProcess, which takes the process name as input and gives us back the PID and a handle to the game:

BOOL GetProcess(IN LPWSTR szProcessName, OUT DWORD* dwProcessId, OUT HANDLE* hProcess);

Inside the function, we start by initialising our outputs and taking a snapshot of all processes:

*dwProcessId = 0;

*hProcess = NULL;

HANDLE hSnapShot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, NULL);

if (hSnapShot == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to create process snapshot: %d\\n", GetLastError());

return FALSE;

}

Next, we prepare a PROCESSENTRY32 structure to hold process info and grab the first process from the snapshot:

PROCESSENTRY32 pe32;

pe32.dwSize = sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32);

if (!Process32First(hSnapShot, &pe32)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to retrieve first process: %d\\n", GetLastError());

CloseHandle(hSnapShot);

return FALSE;

}

Now we can loop through the snapshot and check each process against the one we’re looking for:

do {

if (_wcsicmp(pe32.szExeFile, szProcessName) == 0) {

*dwProcessId = pe32.th32ProcessID;

*hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, *dwProcessId);

if (*hProcess == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to get process: %d\\n", GetLastError());

CloseHandle(hSnapShot);

return FALSE;

}

break;

}

} while (Process32Next(hSnapShot, &pe32));

Finally, we clean up and return whether we succeeded:

CloseHandle(hSnapShot);

if (*dwProcessId == 0 || *hProcess == NULL) {

return FALSE;

}

return TRUE;

In the main function, we can call it like this:

DWORD dwPid;

HANDLE hProcess;

LPWSTR szProcessName = L"AC_client.exe";

if (!GetProcess(szProcessName, &dwPid, &hProcess)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Could not find process: %lu: %d\\n", szProcessName, GetLastError());

return -1;

}

This way, every time we start our program it will automatically attach itself to AssaultCube, ready to read and write memory.

How to Find the Assault Cube Base Address

Now that we have a handle to the Assault Cube process, the next step is to retrieve its base address. Think of the base address as the starting point of the game in memory.

Every offset we uncovered in part 1, such as the local player pointer and entity list, is relative to this base address. Without it, those offsets are meaningless because they need the base to calculate their exact position in memory.

To fetch the base address programmatically, we can rely on this WinAPI call:

- EnumProcessModules: lists all modules (DLLs and executables) loaded into a process. The first one it returns is the main module. In our case,

ac_client.exe.

We’ll wrap this in a helper function:

BOOL GetModuleBaseAddress(IN HANDLE hProcess, OUT ULONG_PTR* lpBaseAddress)

{

HMODULE hMod;

DWORD dwNeeded;

if (EnumProcessModules(hProcess, &hMod, sizeof(hMod), &dwNeeded))

{

*lpBaseAddress = hMod;

return TRUE;

}

*lpBaseAddress = NULL;

return FALSE;

}

If successful, the base address is stored in lpBaseAddress. This is the address we’ll use to apply all the offsets we mapped earlier. Here’s how we call it:

ULONG_PTR lpBaseAddress;

if (!GetModuleBaseAddress(hProcess, &lpBaseAddress)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Getting base address failed: %d\\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

At this point, we’ve got everything we need to start reading real game data. Next step: use the base address to fetch the local player pointer.

Reading the Local Player Pointer in Assault Cube

With the base address secured, our next target is the local player object. This structure stores all of your in-game information, including:

- Health

- Position (head coordinates)

- View angles (yaw & pitch)

To interact with the game its memory, we’ll use two very common WinAPI functions:

- ReadProcessMemory: lets us read raw data from another process;

- WriteProcessMemory: lets us write raw data into another process.

Because we’ll be calling these functions frequently, it’s best to wrap them in helper functions:

BOOL ProcRead(IN HANDLE hProcess, IN ULONG_PTR uAddress, OUT LPVOID lpBuffer, IN SIZE_T nSize)

{

SIZE_T nBytesRead = 0;

if (hProcess == NULL || lpBuffer == NULL || nSize == 0)

{

SetLastError(ERROR_INVALID_PARAMETER);

return FALSE;

}

if (!ReadProcessMemory(hProcess, (LPCVOID)uAddress, lpBuffer, nSize, &nBytesRead))

{

return FALSE;

}

return (nBytesRead == nSize);

}

BOOL ProcWrite(IN HANDLE hProcess, IN ULONG_PTR uAddress, IN LPCVOID lpBuffer, IN SIZE_T nSize)

{

SIZE_T nBytesWritten = 0;

if (hProcess == NULL || lpBuffer == NULL || nSize == 0)

{

SetLastError(ERROR_INVALID_PARAMETER);

return FALSE;

}

if (!WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, (LPVOID)uAddress, lpBuffer, nSize, &nBytesWritten))

{

return FALSE;

}

return (nBytesWritten == nSize);

}

Now, using the ProcRead function, we can fetch the local player pointer.

ULONG_PTR lpLocalPlayer;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, (ULONG_PTR)lpBaseAddress + LOCALPLAYEROFFSET, &lpLocalPlayer, sizeof(lpLocalPlayer))) {

fprintf(stderr, "Reading Process failed: %d\\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

From this point on, lpLocalPlayer is our gateway to all player-related data, health, head coordinates and view angles.

Reading the Entity Count in Assault Cube

The last step before building our aimbot logic is figuring out how many players (or bots) are currently active in the game. We'll call this value the entity count.

Just like the local player pointer, the entity count is stored in memory and can be accessed using our ProcRead helper:

DWORD dwEntityCount;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, (ULONG_PTR)lpBaseAddress + ENTITYLISTCOUNT, &dwEntityCount, sizeof(dwEntityCount)))

{

fprintf(stderr, "Reading Process failed: %d\\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

dwEntityCount now holds the number of active entities in the match. We’ll use it to determine how many times our loop should run when scanning through the entity list.

Understanding Vectors and Data Types in Assault Cube

Now that we've got everything setup, we need to discuss vectors.

A vector is just a collection of numbers that represent a position or a direction in space:

- A Vector2 uses two numbers (x, y), used for, for example, screen positions;

- A Vector3 uses three numbers (x, y, z), used for calculating positions in a 3D game.

Think of a vector as an arrow:

- The tail is at the origin (0,0,0);

- The head points toward (x, y, z).

This arrow tells you both where something is and the direction you need to go to reach it. In code, vectors are represented as follows:

typedef struct Vector3 {

FLOAT x;

FLOAT y;

FLOAT z;

} Vector3;

typedef struct Vector2 {

FLOAT X;

FLOAT Y;

} Vector2;

A players position is stored in a variable of type Vector3. Viewangles, which is the (x,y) combination that determines what we're pointing at, is of type Vector2.

Vector Calculations for Aimbot Targeting

Now that we know what a vector actually is, let’s talk about how we can use them. The following functions help us figure out things like how far away an enemy is or which direction to aim.

Vector3 VectorSubtract(Vector3 a, Vector3 b) {

Vector3 result;

result.x = a.x - b.x;

result.y = a.y - b.y;

result.z = a.z - b.z;

return result;

}

This one’s easy: it subtracts one position from another. The result is an arrow pointing from the vector a to the vector b. This can come in very useful if we want to get the direction from the player we control to the entity.

FLOAT VectorLength(Vector3 v) {

return sqrtf(v.x * v.x + v.y * v.y + v.z * v.z);

}

Here we’re measuring the length of that arrow. This tells us the distance between two points. Shoot an enemy across the map? The number is big. Stand right next to them? The number is small. In fancy terms, this is called a Euclidean length of a 3D vector. Another (better) way of doing this is with the hypot function from math.h:

// Always Works

FLOAT VectorLength(Vector3 v) {

return hypotf(v.x, hypotf(v.y, v.z));

}

// Works since C++ 17

FLOAT VectorLength(Vector3 v) {

return hypotf(v.x, v.y, v.z);

}

This will provide the exact same ouput.

Vector3 VectorNormalize(Vector3 v) {

float length = VectorLength(v);

Vector3 normalized = { 0 };

if (length != 0.0f) {

normalized.x = v.x / length;

normalized.y = v.y / length;

normalized.z = v.z / length;

}

return normalized;

}

This one takes our big arrow and shrinks it down so it’s always length 1. That means it no longer tells us how far away something is, only which direction it’s in. We call this a direction vector.

Vector3 CalculateDirection(Vector3 vPlayerPos, Vector3 vEntityPos) {

Vector3 direction = VectorSubtract(vEntityPos, vPlayerPos);

return VectorNormalize(direction);

}

And finally, this function glues everything together. It figures out the arrow from us to the enemy, and then normalizes it. The result is a clean direction vector pointing straight at the target.

Finding the Closest Entity in Assault Cube

Now that we covered all the mathematics regarding our position and the position of the entity, we can start implementing logic to actually find the closest entity relative from our position.

Get the Player’s Camera Position

We’ll start by grabbing the position of our own player’s head (the “camera” point of view):

Vector3 vPlayerHeadPos;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERHEADPOSOFFSET, &vPlayerHeadPos, sizeof(vPlayerHeadPos))) {

return FALSE;

}

This gives us the exact 3D coordinates of the player’s view, which we’ll use as a reference.

Define the Function

Next, we’ll create a helper function FindClosestEntity. Its job is to scan through all entities, measure distances, and return the closest one.

BOOL FindClosestEntity(IN HANDLE hProcess, IN ULONG_PTR lpBaseAddress, IN Vector3 vPlayerHeadPos, IN DWORD dwEntityCount, OUT Vector3* vClosestEntity);

This function will output a vector3 position of the closest entity relative from our position.

Access the Entity List

Before we loop through the entity list, we'll need to find the entity list and loop over each entity. Therefore we'll first find the entry in memory:

ULONG_PTR lpEntityList;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, (ULONG_PTR)lpBaseAddress + ENTITYLIST, &lpEntityList, sizeof(lpEntityList)))

{

return FALSE;

}

Loop Through Entities

Now we loop through the list, calculate distances, and track the closest entity.

Playing around in it has taught me that the first position is always empty, therefore the iterator will start at 1. We'll also need to add +1 to the amount of entities. Otherwise we'll miss one entity:

FLOAT fClosestEntity = 999999.f;

for (int iEntity = 1; iEntity < dwEntityCount + 1; iEntity++) {

ULONG_PTR lpEntity;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, lpEntityList + (iEntity * sizeof(ULONG_PTR)), &lpEntity, sizeof(lpEntity))) {

return FALSE;

}

Vector3 vEntityPos;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, lpEntity + PLAYERHEADPOSOFFSET, &vEntityPos, sizeof(vEntityPos))) {

return FALSE;

}

FLOAT fEntityDistanceFromPlayer = VectorLength(VectorSubtract(vPlayerHeadPos, vEntityPos));

if (fEntityDistanceFromPlayer < fClosestEntity) {

*lpClosestEntity = lpEntity;

fClosestEntity = fEntityDistanceFromPlayer;

}

}

return TRUE;

}

This function ensures our aimbot is targeting the nearest entity. Without it, the bot might randomly snap to faraway enemies, which isn't practical.

Calculating View Angles in Assault Cube

At this point, we’ve figured out where the closest enemy is in 3D space. But just knowing where they are isn’t enough. If we actually want our aimbot to look at them, we need to convert that position into something the game understands, which are view angles.

Think of view angles as your head movement in the game:

- Yaw: looking left and right;

- Pitch: looking up and down.

Our goal is to manipulate our view angles to point at the entity. To do this we need a couple of functions from the math.h library:

- atan2f: This tells us the angle of a line in a 2D plane. Imagine standing at (0,0) and asking, what “angle do I have to turn to face (x,y)?” That’s exactly what

atan2fgives us; - hypotf: This gives the distance of a point (x,y) from the origin (0,0). Basically, it’s just

sqrt(x² + y²), we've seen it before when calculating vectors too.

atan2f and hypotf work in radians (0 to ~6.28), but games usually use degrees (0°–360°). So we’ll make a helper function:

FLOAT ToDegrees(FLOAT radians) {

return radians * (180.0f / 3.14159265358979323846f);

}

Now, let's first calculate the direction we need to look at.

Vector3 vDirection = CalculateDirection(vPlayerHeadPos, vClosestEntity);

We now have a Vector3 arrow pointing from our camera position to the head of the entity. Next, let's initialize the viewangles variable and start calculating the yaw:

ViewAngles vaViewAngles;

vaViewAngles.Yaw = ToDegrees(atan2f(vDirection.y, vDirection.x)) + 90.f;

For Yaw, we use atan2f(y, x). This gives the horizontal angle, and we add +90.f because in Assault Cube the “0°” reference isn’t perfectly aligned. The only thing left to do now is calculate what pitch (up and down) is needed.

vaViewAngles.Pitch = ToDegrees(atan2f(vDirection.z, hypotf(vDirection.y, vDirection.x)));

For Pitch, we use atan2f(z, hypot(y, x)). hypot(y, x) = distance to the enemy on the ground plane. Compare that with z (the height difference). The result tells us how much to tilt our view up or down.

The last thing we need to do is write these new values to memory. We'll do this like so:

if (!ProcWrite(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERYAWOFFSET, &vaViewAngles.Yaw, sizeof(vaViewAngles.Yaw))) {

return FALSE;

}

if (!ProcWrite(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERPITCHOFFSET, &vaViewAngles.Pitch, sizeof(vaViewAngles.Pitch))) {

return FALSE;

}

Adding a Mouse Hook for Automatic Aimbot Activation

Although this works, we probably don't want to run this program everytime only to look at an enemy once. Therefore, let's make sure, everytime we right-click, we'll aim on the enemy's head automatically.

Install a Mouse Hook

We’ll use the Windows API function SetWindowsHookEx to listen for mouse events. In this case, we’ll hook into WH_MOUSE_LL (low-level mouse events).

g_hHook = SetWindowsHookEx(WH_MOUSE_LL, LowLevelMouseProc, NULL, 0);

if (g_hHook == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to install mouse hook. Error: %lu\\n", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

printf("Right mouse click hook installed. Press Ctrl+C to exit.\\n");

MSG msg;

while (GetMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0)) {

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

}

UnhookWindowsHookEx(g_hHook);

return 0;

}

This code installs the hook, listens for mouse input, and cleans up properly when the program exits.

Handle Right-Click Events

Next, we define our callback function LowLevelMouseProc. Every time the mouse is clicked, this function is triggered. We only care about WM_RBUTTONDOWN (right-click down).

LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelMouseProc(int nCode, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam) {

if (nCode == HC_ACTION) {

if (wParam == WM_RBUTTONDOWN) {

MSLLHOOKSTRUCT* pMouse = (MSLLHOOKSTRUCT*)lParam;

Vector3 vPlayerHeadPos;

if (!ProcRead(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERHEADPOSOFFSET, &vPlayerHeadPos, sizeof(vPlayerHeadPos))) {

return FALSE;

}

Vector3 vClosestEntity;

if (!FindClosestEntity(hProcess, lpBaseAddress, vPlayerHeadPos, dwEntityCount, &vClosestEntity)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed getting closest entity: %d\\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

Vector3 vDirection = CalculateDirection(vPlayerHeadPos, vClosestEntity);

ViewAngles vaViewAngles;

vaViewAngles.Yaw = ToDegrees(atan2f(vDirection.y, vDirection.x)) + 90.f;

vaViewAngles.Pitch = ToDegrees(atan2f(vDirection.z, hypotf(vDirection.y, vDirection.x)));

if (!ProcWrite(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERYAWOFFSET, &vaViewAngles.Yaw, sizeof(vaViewAngles.Yaw))) {

return FALSE;

}

if (!ProcWrite(hProcess, lpLocalPlayer + PLAYERPITCHOFFSET, &vaViewAngles.Pitch, sizeof(vaViewAngles.Pitch))) {

return FALSE;

}

}

}

return CallNextHookEx(g_hHook, nCode, wParam, lParam);

}

Global variables

This new implementation however, will force us to make the following variables global and get them out of the main function.

HANDLE hProcess;

ULONG_PTR lpLocalPlayer;

ULONG_PTR lpBaseAddress;

DWORD dwEntityCount;

Conclusion

In this second part of the Assault cube game hacking series, we’ve transformed theory into practice by building a fully functional aimbot. Using the offsets discovered in part 1, we created a program that can:

- Automatically attach to the game process and grabs its base address;

- Interact with memory using helper functions;

- Use vectors to calculate distances and directions;

- Turn those directions into view angles the game understands;

- Automate it all so a simple right-click snaps to the nearest enemy.

The same principles can also be applied to build ESPs (for example, wallhacks that show enemies through walls). The reversing and coding process would look very similar. Just keep in mind that these kinds of cheats are easily flagged by modern anti-cheat systems, the real value is in learning how the pieces fit together.